Comparative Critique Between Coy Mistress and Sexual Healing

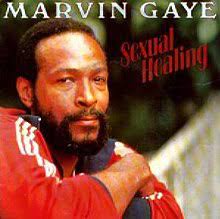

When given the choice to decide between love and death, many would find it difficult to cope with the consequences of their decision. The loss of a beloved or worse the loss of one’s own life can be seriously triggering to those who acknowledge the grip of the reaper coming towards them. Guilty pleasures and the sensual aspects of a relationship are the main focuses for Andrew Marvell in his 1861 carpe diem poem, “To His Coy Mistress”. Marvell relishes in the aspect of death being inevitable and to seize opportunities for sensuality; these words speak in relation to the legendary R&B track, “Sexual Healing” by soul singer Marvin Gaye in 1982. Gaye completely idealizes healing his mental, physical, and emotional wounds through sexual gratification; the tune attempts to connect the sensuality that Marvell pushes for as a health aid that can soothe someone back to normality. Although several centuries apart in their creation, Marvell and Gaye both focus on pushing to obtain sensuality and sexual gratification from partners but differ slightly in their approach on why this sort of pleasure is needed. Marvin Gaye looks to heal his illegitimate wounds as to where Andrew Marvell seeks to gain sexual experiences before death overcomes him.

Published after his death, “To His Coy Mistress” by Andrew Marvell was speculated to be written during the 1640’s-1660’s. This time period is imperative in understanding his worry about the afterlife and not taking his life for granted. Life expectancy, illnesses, and incident-related fatalities were pressing matters that would make anyone born during this time afraid of living accordingly. It is also in theory that during the creation of Marvell’s poem, Marvell was suffering from the adverse effects of Malaria and using this poem to relate his own fear of death and living life to the fullest on paper. The speaker first explains that in a world not bound by the fear of death he and his “coyness, lady,” (2) would spend eternity planning romantics between one another and living every moment as if there was never an end. The speaker then establishes his main priority within the statement, “And you should, if you please, refuse / Till the conversion of the Jews.” (9-10). The speaker is explaining how in this hypothetical situation, he would not care about consummation and would be infatuated for eternity. In contrast to his theoretical world perspective, the speaker begins giving his in-depth view on the reality (that both the speaker and his lover reside in) is plagued by the hands of mortality. He starts with saying, “But at my back I always hear / Time’s wingèd chariot hurrying near;” (21-22), a quote that enables the reader to understand reality and investigate the real world. The speaker goes on to show intentions that are beyond romanticism and aimed towards achieving physical affection, ignoring chastity with his loved one. He goes on to talk about the consequences of not receiving the bounds of pleasures he seeks to find, “The grave’s a fine and private place, / But none, I think, do there embrace.” (31-32). The speaker becomes increasingly more emphatic about his wants and explains how infatuated he is with his Coy Mistress; that her beauty is arousing, and tension built from the feeling of impending doom must be released from engaging in an embrace. Following this event, the speaker ends by proclaiming, “Thus, though we cannot make our sun / Stand still, yet we will make him run.” (45-46), meaning that his lover and him should act accordingly, instead of accepting time as a force that would ruin their ability to live in the memories, they would rather push against the chronological time progression and face every waking moment as if it would be their last.

The poem contains several moments where he contradicts himself as part of a continuous progression of external thoughts that play into the contrast of displaying romanticism in a world that contains no mortality into the real world where the fear of death itself makes the speaker impatient towards abstaining from moral disdain. The reader follows this point from beginning to end when statements saying, “Had we but world enough and time, / This coyness, lady, were no crime.” (1-2), words translated into meaning that if the speaker were not subject to death, he would love endlessly. Then his progression into sheer jealousy when, “[The] worms shall try / That long-preserved virginity,” (27-28), using it as a point to his coy mistress that although her prudishness is a reminder of her vow to godliness, eventually (even in death) it would be captured by someone other than the speaker. As the poem reaches an end, the speaker turns away from seemingly demanding for his lover to consummate their relationship for offering that a life in which they resent time and act on impulse. The quote, “Thus, though we cannot make our sun / and still, yet we will make him run.” (45-46), explains accurately how the speaker keeps the theme of fearing for death to take him and how they must live accordingly because a lifetime of love is not enough to abstain from sensuality.

The speaker in the tune “Sexual Healing” by Marvin Gaye has striking similarities in his intentions to experience gratification through sexual acts. Gaye wrote the tune in 1982, when the age of sensuality and uncensored nature of feelings were expressed in music openly without fear of pushing the boundary. His music leading up to his tragic death usually spoke of love in a predominantly public manner with physical affection being a normal occurring theme. The speaker, instead of fearing for death to ruin the romance in his life, seeks to aid his pain with sexual favors from a favorable partner. He speaks of sexual healing in many forms in the first bridge he begins with emotional healing when he says, “Whenever blue teardrops are falling / And my emotional stability is leaving me” (16-17). He plans to fix his emotional pain by calling upon his lover for sexual healing, a recurring phrase that is repeated after every scenario the speaker creates when explaining his wounds. After explaining the emotional side of healing he would receive, the speaker goes on to explain how his physical aches and bounds could be soothed by his lover, “Baby, I got sick this morning /A sea was storming inside of me” (28-29). Whenever he experiences any form of pain from his “body and mind” (42), he asks for his lover to heal him through sexual healing, an aid in which his scars will be relieved illegitimately. Another similarity to the speaker in “To His Coy Mistress,” Gaye’s speaker includes a portion where he pleads for the gratification he seeks to find. He metaphorically explains that his lover is medicine that will heal him, but later goes to say how “[He] can’t wait for [her] to operate” (46), comparing her to a doctor who will oversee his recovery. He ends his pleading by explaining that any other form of sexual gratification whether it be personal means or abstaining would not suffice, he wants to be healed by the lover he seems to appreciate endearingly.

The speakers in both “Sexual Healing” and “To His Coy Mistress” are similar in their intentions but are different in their approach as to why they desire this release. Marvell’s poem contains a sharp change where the speaker changes from romantic to sexual desire due to the fear of death itself and not living life to its fullest extent. Gaye’s poem contains a repeated message that in all forms of pain that the speaker experiences the sexual desire can heal and bring him peace. One’s motivation is to experience pleasure before death consumes him and one looks to guide his lover into healing him from pains that haunt him. Whether the sexual healing or fighting against time by living in the moment is legitimate motives to experience sex, the speakers are passionate and speak directly to their significant others as if they are directly asking them. Overall, both poems attempt to convey themes of life, love, and death. They also explain motivations behind wanting the feeling of sensuality. They use terms of endearment, and they explain attachment to those they want to experience these feelings with. Marvell and Gaye show differences in their overall universal outtake from their poems. Marvell shows how when presented with the certainty of death instead of cowering and live in fear of what is to come; relish in every moment. Gaye demonstrates a different message through what happens during one’s lifetime, how when life takes a toll on the body, one should take time to heal and take time slow. The difference in the poems on a large scale is major but, looking intrinsically the two poets have created poems that complement each other in their meaning and the speaker actions.